Is it time to amend Anti-Defection Laws ?

~Preet.

Recently, the Vice-President stated that the time has come to modify the country's anti-defection legislation to close current loopholes. Individual Members of Parliament (MPs)/MLAs are punished under the anti-defection statute for defecting from one party to another. In 1985, Parliament inserted it to the Constitution as the Tenth Schedule. Its goal was to keep governments stable by deterring MPs from switching parties. The Tenth Schedule, often known as the Anti-Defection Act, was included into the Constitution by the 52nd Amendment Act of 1985. It establishes the procedures for disqualifying elected members for defecting to another political party. It was a reaction to the overthrow of various state administrations by party-hopping MLAs following the 1967 federal elections. It enables a group of MPs/MLAs to join (i.e., combine with) another political party without incurring the defection penalty. Furthermore, political parties are not penalised for soliciting or tolerating defecting legislators. According to the 1985 Act, a 'defection' by one-third of a political party's elected members was considered a'merger.' However, the 91st Constitutional Amendment Act of 2003 modified this, and now at least two-thirds of a party's members must be in favour of a "merger" for it to be legal. Members who are disqualified under the legislation can run for a seat in the same House from any political party. The decision for disqualification on the basis of defection is reported to the Chairman or Speaker of such House, and is subject to 'Judicial review.' The statute, however, does not specify a timeline within which the presiding officer must rule on a defection case.

If an elected official willingly withdraws from a political party. If he votes or abstains from voting in such House in defiance of any directive issued by his political party or anybody authorised to do so without first receiving authorization. His abstention from voting should not be accepted by his party or the authorised person within 15 days of the occurrence as a precondition for his disqualification. If a member who was elected independently joins a political party. If any nominated person joins a political party after the six-month period has expired.

Following the implementation of the Anti-defection law, the MP or MLA must blindly follow the party's instructions and has no flexibility to vote in their own opinion. The chain of responsibility has been disrupted as a result of the Anti-Defection statute, which holds MPs solely accountable to their political party. There is no clarity in the legislation about the timetable for the House Chairperson or Speaker to act in anti-defection matters. Some cases take six months, while others take three years. There are certain instances that are resolved after the term has ended. The anti-defection statute was amended in the 91st amendment to include an exemption for anti-defection judgements. The amendment, however, does not recognise a'split' in a legislature party, but rather a'merger.'

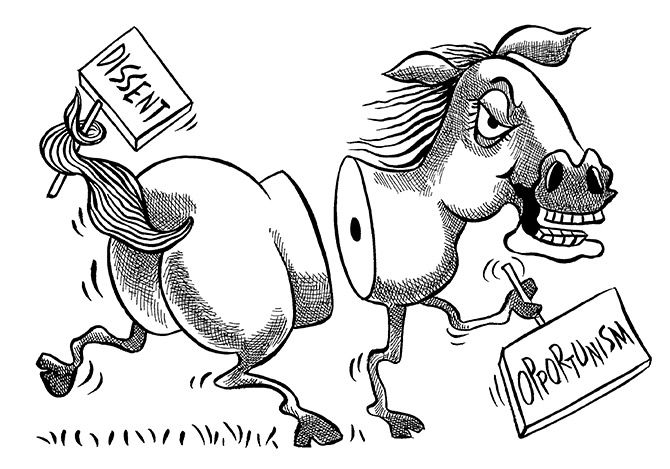

Defection is the subversion of election mandates by lawmakers who are elected on one party's ticket but then find it more convenient to switch to another owing to the temptation of cabinet slots or financial benefits. The iconic "Aaya Ram, Gaya Ram" slogan was coined in the 1960s against the backdrop of constant lawmaker defections. The defection causes instability in the government and has an impact on the administration. Defection also encourages legislator horse-trading, which obviously contradicts the mission of a democratic structure. It enables wholesale defection but not retail defection. To close the gaps, amendments are necessary.

The Election Commission has proposed that it be the determining authority in situations of defection. Others have suggested that defection petitions should be heard by the President and Governors. The Supreme Court has proposed that Parliament establish an independent panel, led by a retired judge from the higher court, to hear defection cases quickly and impartially. Some observers have suggested that the law has failed and that it should be repealed. Former Vice President Hamid Ansari has claimed that it only applies in no-confidence resolutions to rescue administrations.

The issue stems from the attempt to find a legal solution to what is fundamentally a political issue. If government stability is a concern as a result of people defecting from their parties, the solution is for parties to enhance their internal structures. In India, there is an urgent need for law that oversees political parties. A bill of this type would subject political parties to the Right to Information (RTI), promote intra-party democracy, and so forth. To mitigate the negative impact of the anti-defection legislation on representative democracy, the law's scope might be limited to just those laws where the defeat of government can lead to a loss of trust.

Comments

Post a Comment